Goodbye, adios, 再见, 2020! As we enter 2021, I’m fully aware that there are things that I cannot change. The Great Mask-Wearing Debacle rages on (despite the science that has proven again and again that masks! stop! the! spread! of! COVID-19!). The longest, most painful transition of power between US presidents ever, with every person political or otherwise calling foul on some front. The ever-dividing rift between Democrats and Republicans, worsened by Trump’s careless tweets and mishandling of nearly every issue under the sun (BLM, climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, just to name a few).

But there are things that I am in control of. I can start new crafts. I can write more poems and maybe take a swing at getting into an MFA program again. I can exercise more and stretch often. I can learn to do more than just basic chord strums on the ukulele. I didn’t quite hit my reading goal for last year (40 books), but I can try to get there this year. I can continue to hope that things will heal and that our current state of events will get better. And I’m re-re-resurrecting this blog! Maybe this will be my only post of the year, maybe I’ll get into a new rhythm of posts, but either way, I’m here now!

For my first (and maybe only) post of 2020, I’m going to recount the books I have read in the past year, making special note of my top ten:

- N0S4A2- Joe Hill

- Where the Crawdads Sing- Delia Owens; Beautiful beautiful. Chances are you’ve heard of this one. This book has been a top book club book since it was released in 2018, and I had to wait over a month to get off my library’s waitlist. It’s worth the hype. Kya, the Marsh Girl, learns to fend for herself in the swamp, eventually overcoming the odds and prejudices people have of her. This book is gentle and rugged in all the right ways. As a book that so intimately deals with instinct and nature, it also reveals the tenderness and ruthlessness of the human spirit. So many lyrical lines that ring through the reader like bird song.

- Exhalation- Ted Chiang

- Americanah- Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche

- The Disappearing Spoon- Sam Kean

- Dune- Frank Herbert

- A Man Called Ove- Frederik Backman; For those who know me, it’s no surprise that the Backman book I read this year made it on my top ten. Beartown (also by him) is one of my favorite books ever. A Man Called Ove is funnier, but an emotional rollercoaster nonetheless. If ever there is a time where you forget that people can be kind: read a Backman book. Heart-swelling and eye-watering.

- The Glass Hotel- Emily St. John Mandel; Perhaps also skewed by my love for Station Eleven, this book by Mandel is another top pick for 2020. Mandel is a fantastic author. She pulls characters and timelines together with the strategy of a chess player but the deftness of a dancer. This story follows a Ponzi scheme and all the lives that topple as the scheme falls apart. The characters imagine a counterlife, how things would be different if they had made different choices. 2020 was a year of what-ifs, and this book embodies that feeling of haunted uncertainty.

- Before the Devil Breaks You- Libba Bray

- Run Away- Harlan Coben; Reflecting back on this book now, I’m reminded of how absolutely insane it is. Simon Greene’s daughter Paige is a drug addict. She’s homeless. She’s missing. Simon goes to incredible lengths to figure out what happened to her and bring her home safely. This novel moves at breakneck speed, so fast you can’t even question what you’ve read. I was wholly invested in Simon’s quest and the larger web of secrets he stumbles into. This is an action-centric thriller that builds and builds and builds and is almost impossible to put down.

- The Happy Prince and Other Tales- Oscar Wilde

- The Trials of Apollo- Rick Riordan

- The Sign of Four- Arthur Conan Doyle

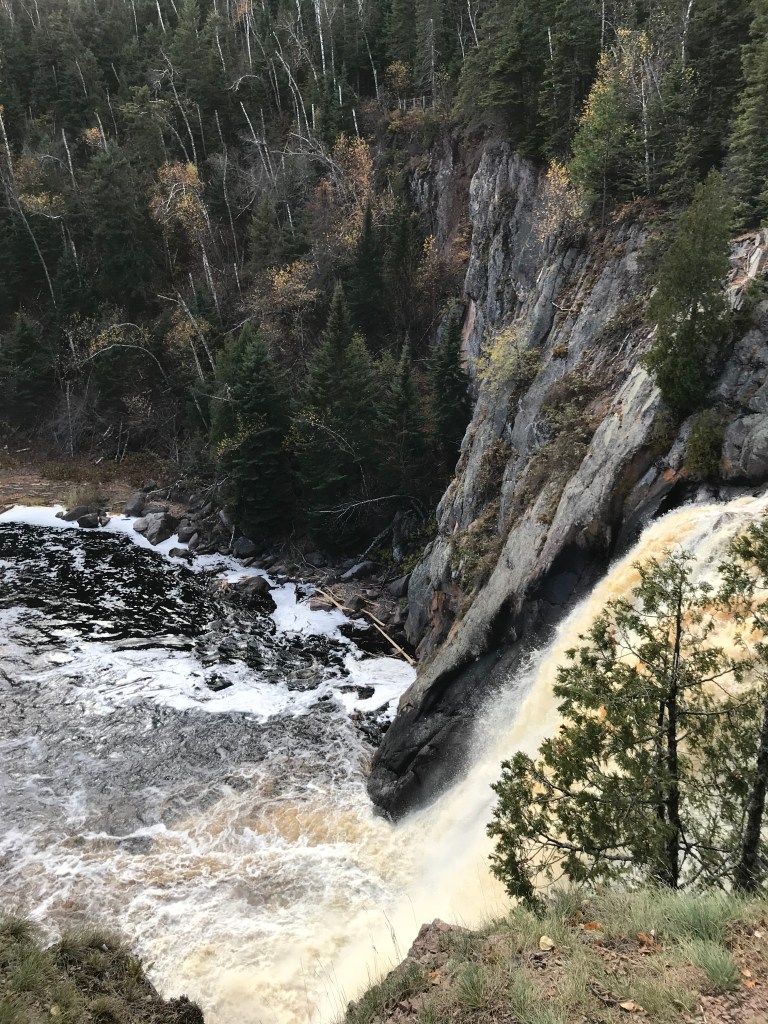

- The Years of the Forest- Helen Hoover; This is a memoir about Hoover’s years living in Northern Minnesota. I’ve never read anything like this, and I’ve never really imagined what it would be like to live almost entirely self-sufficiently, secluded from everybody else. Spoiler alert: it ain’t easy. What I like most about this book is that it shows a way that people can live in harmony with nature. We can’t all go to the same lengths as Hoover and her husband, but we can make an effort to be conscious about our actions and how they impact the world around us. Is our right to the Earth any greater than the creatures around us?

- The Inside Game- Keith Law

- Les Miserables- Victor Hugo; I’m going to be an English major nerd for a hot sec and say that this is my favorite book of 2020. I had avoided reading it for a long time because the length terrified me. My advice to you: don’t let the length scare you away! Especially if you’ve watched the musical or movie or listened to the soundtrack, this is an extremely palatable read. Hugo doesn’t hide where his morals lie, and that makes this novel fairly accessible. This is a dramatic novel that touches on topics that will always be important to humankind: poverty, femininity, education, forgiveness, religion, love, revolution. When I had just finished reading this book, I didn’t think I would ever reread it, because it is an investment of time. But if somebody wanted to book club this masterpiece with me, I’d be all over that.

- Normal People- Sally Rooney

- Cat’s Cradle- Kurt Vonnegut

- Call Down the Hawk- Maggie Stiefvater

- A River Runs Through It- Norman Maclean

- Redhead by the Side of the Road- Anne Tyler

- The Tradition- Jericho Brown; Exactly the kind of emotional range that I want in a poetry collection. These poems are hopeful and despairing, careful and angry. The collection is about Blackness and queerness, but they’re not just personal to Brown, they’re not just written for other Black and queer folx. I truly think there’s something in these poems for everyone. All I can think to describe this collection is the slow glow of a hot coal, sometimes embering toward outrage and other times warming to love and hope.

- The Guest List- Lucy Foley

- Murder on the Orient Express- Agatha Christie

- Fathoms- Rebecca Giggs

- Ask Again, Yes- Mary Beth Keane; My favorite literary fiction read of the year. I’m a huge sucker for character studies, and this is a good one. This book is a reminder that healing takes time and that loving can be hard. There’s a tomorrow, and maybe it will be worse, or maybe it will be better in a way that you weren’t expecting.

- A Thousand Endings and Beginnings- ed. Ellen Oh

- Journey to the West- ed. Timothy Richard and Daniel Kane

- Migrations- Charlotte McConaghy

- When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities- Chen Chen; Delightful. For anybody who has reservations about poetry or thinks of it as boring– put this juicy line on your tongue: Dreaming of one day being as fearless as a mango. Absolutely delectable. This collection is youthful, absurd, honest. Some of the poems are soul-bearing and sad, but Chen’s words are never lethargic. This collection gave my heart the happy swims.

- Barkskins- Annie Proulx

- The City We Became- N. K. Jemisin; I’ve never read anything like this. The pure, imaginative prowess of Jemisin’s book should be enough to put this on your radars. Cities that tear through the multiverse to come alive? Baddies that are personified as white hysteria? POC coming together to kick butt? Some of the scenes had my heart racing, and I was seized by a cold terror that some horror novels don’t manage to pull off. Unlike a Stephen King novel, the evils of this book are real threats that could very well tear our actual nation apart. An important, spine-chilling book for novice fantasy readers like myself.

- Splinters Are Children of Wood- Leia Penina Wilson

- White Elephant- Trish Harnetieaux

And that’s a wrap on 2020! If you have any overlap with the titles on this list, I’m always looking for more bookish friends. What were your top reads of the past year? What books are you looking forward to digging into as 2021 begins? Will I continue making posts on this blog? Only time will tell!